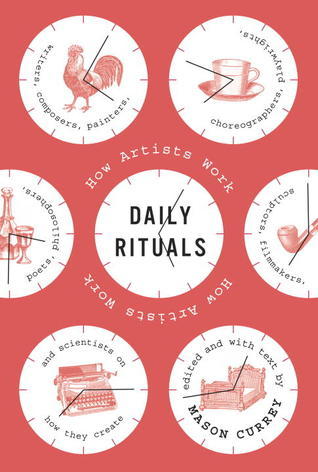

Daily Rituals: How Artists Work

ISBN: 9780307273604

Date read: 2023-11-09

How strongly I recommend it: 6.5/10

Get the book or see my list of books

My notes

He procrastinated. As he told one of his classes, "I know a person who will poke the fire, set chairs straight, pick dust specks from the floor, arrange his table, snatch up a newspaper, take down any book which catches his eye, trim his nails, waste the morning anyhow, in short, and all without premeditation—simply because the only thing he ought to attend to is the preparation of a noonday lesson in formal logic which he detests."

a letter Kafka sent to his beloved Felice Bauer in 1912. Frustrated by his cramped living situation and his deadening day job, he complained, "time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle maneuvers."

A modern stoic," he observed, "knows that the surest way to discipline passion is to discipline time: decide what you want or ought to do during the day, then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble."

which he always did in his home on the remote island of Fårö, Sweden

It was my practice to be at my table every morning at 5.30 A.M.; and it was also my practice to allow myself no mercy. An old groom, whose business it was to call me, and to whom I paid £5 a year extra for the duty, allowed himself no mercy. During all those years at Waltham Cross he never was once late with the coffee which it was his duty to bring me. I do not know that I ought not to feel that I owe more to him than to any one else for the success I have had. By beginning at that hour I could complete my literary work before I dressed for breakfast.

I always began my task by reading the work of the day before, an operation which would take me half an hour, and which consisted chiefly in weighing with my ear the sound of the words and phrases.... This division of time allowed me to produce over ten pages of an ordinary novel volume a day, and if kept up through ten months, would have given as its results three novels of three volumes each in the year;—the precise amount which so greatly acerbated the publisher in Paternoster Row, and which must at any rate be felt to be quite as much as the novel-readers of the world can want from the hands of one man.

Marx was, by 1858, already several years into Das Kapital, the massive work of political economy that would occupy the rest of his life. He never had a regular job. "I must pursue my goal through thick and thin and I must not allow bourgeois society to turn me into a money-making machine," he wrote in 1859.

The meal was, to Mahler’s preference, light, simple, thoroughly cooked, and minimally seasoned. "Its purpose was to satisfy without tempting the appetite or causing any sensation of heaviness,"

When he is writing a novel, Murakami wakes at 4:00 A.M. and works for five to six hours straight. In the afternoons he runs or swims (or does both), runs errands, reads, and listens to music; bedtime is 9:00. "I keep to this routine every day without variation," he told The Paris Review in 2004. "The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind

the "great thing" in education is to "make our nervous system our ally instead of our enemy."The more of the details of our daily life we can hand over to the effortless custody of automatism, the more our higher powers of mind will be set free for their own proper work. There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation

"time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle maneuvers."

P. G. Wodehouse (1881–1975)

We have failed to recognize our great asset: time. A conscientious use of it could make us into something quite amazing."

It is said that some artists abuse their need for coffee, alcohol, or opium. I do not really believe that, and if it sometimes amuses them to create under the influence of substances other than their own intoxicating thoughts, I doubt that they kept up such lubrications or showed them off. The work of the imagination is exciting enough, and I confess I have only been able to enhance it with a dash of milk or lemonade, which would hardly qualify me as Byronic. Honestly, I do not believe in a drunk Byron writing beautiful verses. Inspiration can pass through the soul just as easily in the midst of an orgy as in the silence of the woods, but when it is a question of giving form to your thoughts, whether you are secluded in your study or performing on the planks of a stage, you must be in total possession of yourself.

Balzac drove himself relentlessly as a writer, motivated by enormous literary ambition as well as a never-ending string of creditors and endless cups of coffee; as Herbert J. Hunt has written, he engaged in "orgies of work punctuated by orgies of relaxation and pleasure." When Balzac was working, his writing schedule was brutal: He ate a light dinner at 6:00 P.M., then went to bed. At 1:00 A.M. he rose and sat down at his writing table for a seven-hour stretch of work. At 8:00 A.M. he allowed himself a ninety-minute nap; then, from 9:30 to 4:00, he resumed work, drinking cup after cup of black coffee. (According to one estimate, he drank as many as fifty cups a day.) At 4:00 P.M. Balzac took a walk, had a bath, and received visitors until 6:00, when the cycle started all over again. "The days melt in my hands like ice in the sun," he wrote in 1830. "I’m not living, I’m wearing myself out in a horrible fashion—but whether I die of work or something else, it’s all the same."

Victor Hugo (1802–1885)When Napoléon III seized control of France in 1851, Hugo was forced into political exile, eventually settling with his family on Guernsey, a British island off the coast of Normandy. In his fifteen years there Hugo would write some of his best work, including three collections of poetry and the novel Les Misérables. Shortly after arriving on Guernsey, Hugo purchased Hauteville House—locals believed it was haunted by the ghost of a woman who had committed suicide—and set about making several improvements to the property. Chief among them was an all-glass "lookout" on the roof that resembled a small, furnished greenhouse. This was the highest point on the island, with a panoramic view of the English Channel; on clear days, you could see the coast of France. There Hugo wrote each morning, standing at a small desk in front of a mirror.He rose at dawn, awakened by the daily gunshot from a nearby fort, and received a pot of freshly brewed coffee and his morning letter from Juliette Drouet, his mistress, whom he had installed on Guernsey just nine doors down from Hauteville House. After reading the passionate words of "Juju" to her "beloved Christ," Hugo swallowed two raw eggs, enclosed himself in his lookout, and wrote until 11:00 A.M. Then he stepped out onto the rooftop and washed from a tub of water left out overnight, pouring the icy liquid over himself and rubbing his body with a horsehair glove. Townspeople passing by could watch the spectacle from the street—as could Juliette, looking out the window of her room.

He rose at 7:00, had breakfast at 8:00, and was in his study by 9:00. He stayed there until 2:00, taking a brief break for lunch with his family, during which he often seemed to be in a trance, eating mechanically and barely speaking a word before hurrying back to his desk. On an ordinary day he could complete about two thousand words in this way, but during a flight of imagination he sometimes managed twice that amount. Other days, however, he would hardly write anything; nevertheless, he stuck to his work hours without fail, doodling and staring out the window to pass the time.

"I must write each day without fail, not so much for the success of the work, as in order not to get out of my routine." This is Tolstoy in one of the relatively few diary entries he made during the mid-1860s, when he was deep into the writing of War and Peace.

If the soil is favourable—that is, if I am in the mood for work, this seed takes root with inconceivable strength and speed, bursts through the soil, puts out roots, leaves, twigs, and finally flowers: I cannot define the creative process except through this metaphor. All the difficulties lie in this: that the seed should appear, and that it should find itself in favourable circumstances. All the rest happens of its own accord. It would be futile for me to try and express to you in words the boundless bliss of that feeling which envelops you when the main idea has appeared, and when it begins to take definite forms. You forget everything, you are almost insane, everything inside you trembles and writhes, you scarcely manage to set down sketches, one idea presses upon another.

apparently never lacked for discipline. "Discipline is an ideal for the self," he once said. "If you have to discipline yourself to achieve art, you discipline yourself."